Pixels and their neighbors: Finite volume

| This tutorial originally appeared as a featured article in The Leading Edge in August 2016 — see issue. |

We take you on the journey from continuous equations to their discrete matrix representations using the finite-volume method for the direct current (DC) resistivity problem. These techniques are widely applicable across geophysical simulation types and have their parallels in finite element and finite difference. We show derivations visually, as you would on a whiteboard, and have provided an accompanying notebook at http://github.com/seg to explore the numerical results using SimPEG.[1]

DC resistivity

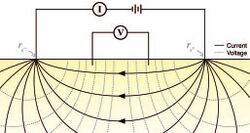

DC resistivity surveys obtain information about subsurface electrical conductivity, . This physical property is often diagnostic in mineral exploration, geotechnical, environmental, and hydrogeologic problems, where the target of interest has a significant electrical conductivity contrast from the background. In a DC resistivity survey, steady-state currents are set up in the subsurface by injecting current through a positive electrode and completing the circuit with a return electrode (Figure 1). The equations for DC resistivity are derived in Figure 2. Conservation of charge (which can be derived by taking the divergence of Ampere's law at steady state) connects the divergence of the current density everywhere in space to the source term, which consists of two point sources, one positive and one negative. The flow of current sets up electric fields according to Ohm's law, which relates current density to electric fields through the electrical conductivity. From Faraday's law for steady-state fields, we can describe the electric field in terms of a scalar potential, , which we sample at potential electrodes to obtain data in the form of potential differences.

To set up a solvable system of equations, we need the same number of unknowns as equations, in this case two unknowns (one scalar, , and one vector, ) and two first-order equations (one scalar, one vector).

In this tutorial, we walk through setting up these first-order equations in finite volume in three steps: (1) defining where the variables live on the mesh; (2) looking at a single cell to define the discrete divergence and the weak formulation; and (3) moving from a cell-based view to the entire mesh to construct and solve the resulting matrix system. The notebooks included with this tutorial leverage the SimPEG package, which extends the methods discussed here to various mesh types.[1]

Where do things live?

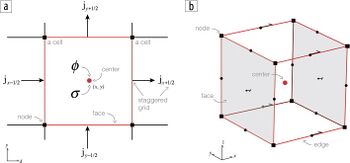

To bring our continuous equations into the computer, we need to discretize the earth and represent it using a finite set of numbers. In this tutorial, we will explain the discretization in 2D and generalize to 3D in the notebooks. A 2D (or 3D) mesh is used to divide up space, and we can represent functions (fields, parameters, etc.) on this mesh at a few discrete places: the nodes, edges, faces, or cell centers. For consistency between 2D and 3D, we refer to faces having area and cells having volume, regardless of their dimensionality. Nodes and cell centers naturally hold scalar quantities, while edges and faces have implied directionality and therefore naturally describe vectors. The conductivity, , changes as a function of space and is likely to have discontinuities (e.g., if we cross a geologic boundary). As such, we will represent the conductivity as a constant over each cell and discretize it at the center of the cell. The electrical current density, , will be continuous across conductivity interfaces, and therefore, we will represent it on the faces of each cell. Remember that is a vector; the direction of it is implied by the mesh definition (i.e., in x, y, or z), so we can store the array j as scalars that live on the face and inherit the face's normal. When is defined on the faces of a cell, the potential, , will be put on the cell centers. (Since is related to through spatial derivatives, it allows us to approximate centered derivatives leading to a staggered, second-order discretization.) Once we have the functions placed on our mesh, we look at a single cell to discretize each first-order equation. For simplicity in this tutorial, we will choose to have all of the faces of our mesh be aligned with our spatial axes (x, y, and z); the extension to curvilinear meshes will be presented in the supporting notebooks at http://github.com/seg.

One cell at a time

To discretize the first-order differential equations (Figure 2), we consider a single cell in the mesh, and we will work through the discrete description of equations (a) and (b) over that cell.

(1) In and out

Equation (a) relates the divergence of the current density to a source term. To discretize using finite volume, we will look at the divergence geometrically. The divergence is the integral of a flux through a closed surface as that enclosed volume shrinks to a point. Since we have discretized and no longer have continuous functions, we cannot fully take the limit to a point; instead, we approximate it around some (finite) volume: a cell. The flux out of the surface () is actually how we discretized onto our mesh (i.e., j) except that the face normal points out of the cell (rather than in the axes direction). After fixing the direction of the face normal (multiplying by ± 1), we only need to calculate the face areas and cell volume to create the discrete divergence matrix.

So we have half of the equation discretized — the left-hand side. Now we need to take care of the source: it contains two dirac delta functions — these are infinite at their origins, and (infinity is not exactly something a computer does well with!). However, the volume integral of a delta function is well defined: it is unity if the volume contains the origin of the delta function; otherwise, it is zero. As such, we can integrate both sides of the equation over the volume enclosed by the cell. Since is constant over the cell, the integral is simply a multiplication by the volume of the cell . The integral of the source is zero unless one of the source electrodes is located inside the cell, in which case it is . Now we have a discrete description of equation (a) over a single cell:

()

(2) Scalar equations only, please

Equation 2 is a vector equation, so really it is two or three equations involving multiple components of . We want to work with a single scalar equation, allow for anisotropic physical properties, and potentially work with non-axis-aligned meshes — how do we do this?! We can use the weak formulation where we take the inner product () of the equation with a generic face function, . This reduces requirements of differentiability on the original equation and also allows us to consider tensor anisotropy or curvilinear meshes.[2]

In Figure 5, we visually walk through the discretization of equation 2. On the left-hand side, a dot product requires a single cartesian vector, []. However, we have a j defined on each face ( and in 2D). There are many different ways to evaluate this inner product: we could approximate the integral using trapezoidal, midpoint, or higher-order approximations. A simple method is to break the integral into four sections (or eight in 3D) and apply the midpoint rule for each section using the closest components of j to compose a cartesian vector. A matrix (size 2 × 4) is used to pick out the appropriate faces and compose the corresponding vector. (These matrices are shown with colors corresponding to the appropriate face in Figure 5.) On the right-hand side, we use a vector identity to integrate by parts. The second term will cancel over the entire mesh (as the normals of adjacent cell faces point in opposite directions) and on mesh boundary faces are zero by the Dirichlet boundary condition. (We are using Dirichlet for simplicity in this example; in practice, Neumann conditions are often used. This is because “infinity” needs to be further away if applying Dirichlet boundary conditions since potential falls off as and current density as .) This leaves us with the divergence, which we already know how to do!

The final step is to recognize that, now that the equation is discretized, we can cancel the general face function f and transpose the result (for convention's sake):

All together now

We have now discretized the two first-order equations over a single cell. What is left is to assemble and solve the DC system over the entire mesh. To implement the divergence on the full mesh, the stencil of ± 1′s must index into j on the entire mesh (instead of four elements). Although this can be done in a for-loop, it is conceptually, and often computationally, easier to create this stencil using nested kronecker products (see notebook). The volume and area terms in the divergence get expanded to diagonal matrices, and we multiply them together to get the discrete divergence operator. The discretization of the face inner product can be abstracted to a function, , that completes the inner product on the entire mesh at once. The main difference when implementing this is the P matrices, which must index into the entire mesh.

With the necessary operators defined for both equations on the entire mesh, we are left with two discrete equations

()

Note that now all variables are defined over the entire mesh. We could solve this coupled system or we could eliminate j and solve for directly (a smaller, second-order system).

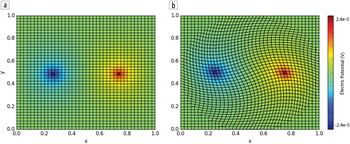

()

By solving this system matrix, we obtain a solution for the electric potential everywhere in the domain. Creating predicted data from this requires an interpolation to the electrode locations and subtraction to obtain potential differences!

Moving from continuous equations to their discrete analogues is fundamental in geophysical simulations. In this tutorial, we have started from a continuous description of the governing equations for the DC resistivity problem, selected locations on the mesh to discretize the continuous functions, constructed differential operators by considering one cell at a time, and assembled and solved the discrete DC equations. Composing the finite-volume system in this way allows us to move to different meshes and incorporate various types of boundary conditions that are often necessary when solving these equations in practice.

Corresponding author

- Rowan Cockett,

rcockett eos.ubc.ca

eos.ubc.ca

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cockett, Rowan, S. Kang, L. J. Heagy, A. Pidlisecky, and D. W. Oldenburg, 2015, SimPEG: An open source framework for simulation and gradient based parameter estimation in geophysical applications: Computers & Geosciences, 85, 142–154, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2015.09.015

- ↑ Haber, E., 2014, Computational methods in geophysical electromagnetics: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611973808

External links

You can find all the data and code to work through this tutorial for yourself at https://github.com/seg.